The right to live a free life

Efforts to combat negative social control, honour-related violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation are a priority area in the government’s integration strategy (Ministry of Education and Research, 2018).

Negative social control and honour-related violence are barriers to the right to live a free life. The Action Plan Freedom from negative social control and honour-related violence (2021–2024) defines negative social control as pressure, supervision, threats or coercion that systematically restricts someone in their life or repeatedly prevents them from making independent choices about their own life and future. When assessing whether a type of behaviour constitutes negative social control, consideration shall be given to the age and development of the controlled party, as well as to the principle of the child’s best interests (Ministry of Education and Research, 2021).

What are negative social control and honour-related violence?

Honour-related violence, forced marriage and female genital mutilation are all forms of abuse in close relationships. Honour-related violence is defined as violence triggered by a family’s need to protect or restore its honour or social reputation. It occurs in families with strong collectivist and patriarchal values. Girls are particularly vulnerable, because their sexual behaviour is inextricably linked to the honour of the family, and because departure from accepted behaviour can bring shame on the entire family. Forced marriage is defined as marriage where one or both of the parties do not have the opportunity to choose to remain unmarried without being subjected to violence, deprivation of liberty, other criminal or improper conduct, or undue pressure.

Members of the extended family living in countries other than Norway can have a strong influence on the upbringing of and expectations imposed on cross-cultural young people growing up in a collectivist family structure in Norway. In consequence, negative social control and honour-related violence are considered transnational phenomena.

Who and how many are at risk?

The work to combat negative social control and honour-related violence is about preventing and detecting restrictions on freedom, lack of equality and abuse in close relationships for vulnerable children, young people and adults. Negative social control and honour-related violence often occur in a gender perspective, where young people who do not conform with the norms of their extended family may be particularly at risk. Girls may have restrictions imposed on their freedom and other forms of violence and control. Boys can also be victims of this, at the same time as they may also experience pressure to exercise negative social control against their siblings. Young LGBTIQ+ people of either sex may also be at risk of negative social control and honour-related violence.

Negative social control and honour-related violence can occur among newly arrived refugees and in groups of immigrants with a long period of residence in Norway. Certain groups of immigrants are more susceptible to this type of violence and control. Young people who have parents born in the Middle East, North Africa, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and South and East Asia are more likely to experience negative social control (Friberg & Bjørnset, 2019). At the same time, these phenomena are not limited to any individual groups, but rather affect different parts of the population.

Children and young people who are subjected to negative social control and honour-related violence are entitled to receive the help they need at the first opportunity. The support services’ knowledge and skills in this area are being built up on a continuous basis through the relevant action plans. The special assistance services against negative social control and honour-related violence have been strengthened through the expansion of the Directorate of Integration and Diversity (IMDi)’s minority adviser scheme and the establishment of the specialist team for the prevention of negative social control and honour-related violence (IMDi, 2020c). The focus on prevention and detection of control and violence means that more vulnerable people are being identified and helped. At the same time, it is realistic to assume that there are probably more victims of violence and control than are currently captured by the support system (Bredal et al., 2020).

Negative social control and honour-related violence in a transnational

perspective

Many Norwegian children and young people grow up in transnational families, where the extended family in another country exert an influence on how children in the family in Norway are raised. Transnational family life can have both a positive and a negative effect for cross-cultural children and young people. In cases where children and young people in Norway challenge the norms and expectations of the extended family, they may experience negative social control and honour-related violence in a transnational perspective. Children and young people are sometimes sent abroad against their will, where they may be subjected to deprivation of liberty, female genital mutilation or forced marriage. The transnational perspective is reflected in the organisation of the special assistance services to prevent negative social control and honour-related violence, in that the services are based in Norway and at four foreign service missions.

Young people with a minority background and parental restrictions

One indicator of negative social control is the extent to which parents impose restrictions on their children’s self-determination over their own body, freedom to choose their friends, how they spend their free time, religion, how they dress, education, relationships and marriage. A study conducted by the social science research foundation Fafo in 2019 examines the extent of various forms of parental restrictions on young people’s social life and who is most at risk. In the survey, 29 per cent of the girls with a background from Pakistan in the first year of upper secondary school in Oslo and Akershus stated that it is very good or fairly good that their parents do not want them to “spend time with someone of the opposite sex in their spare time, without the presence of an adult”. Among the girls with a background from Somalia and Sri Lanka, the proportion was 23 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively (Friberg & Bjørnset, 2019).

Another analysis examining parental restrictions among young people in Oslo points out that restrictions on activities and relationships in their spare time are far more common than restrictions related to school (Smette et al., 2021).

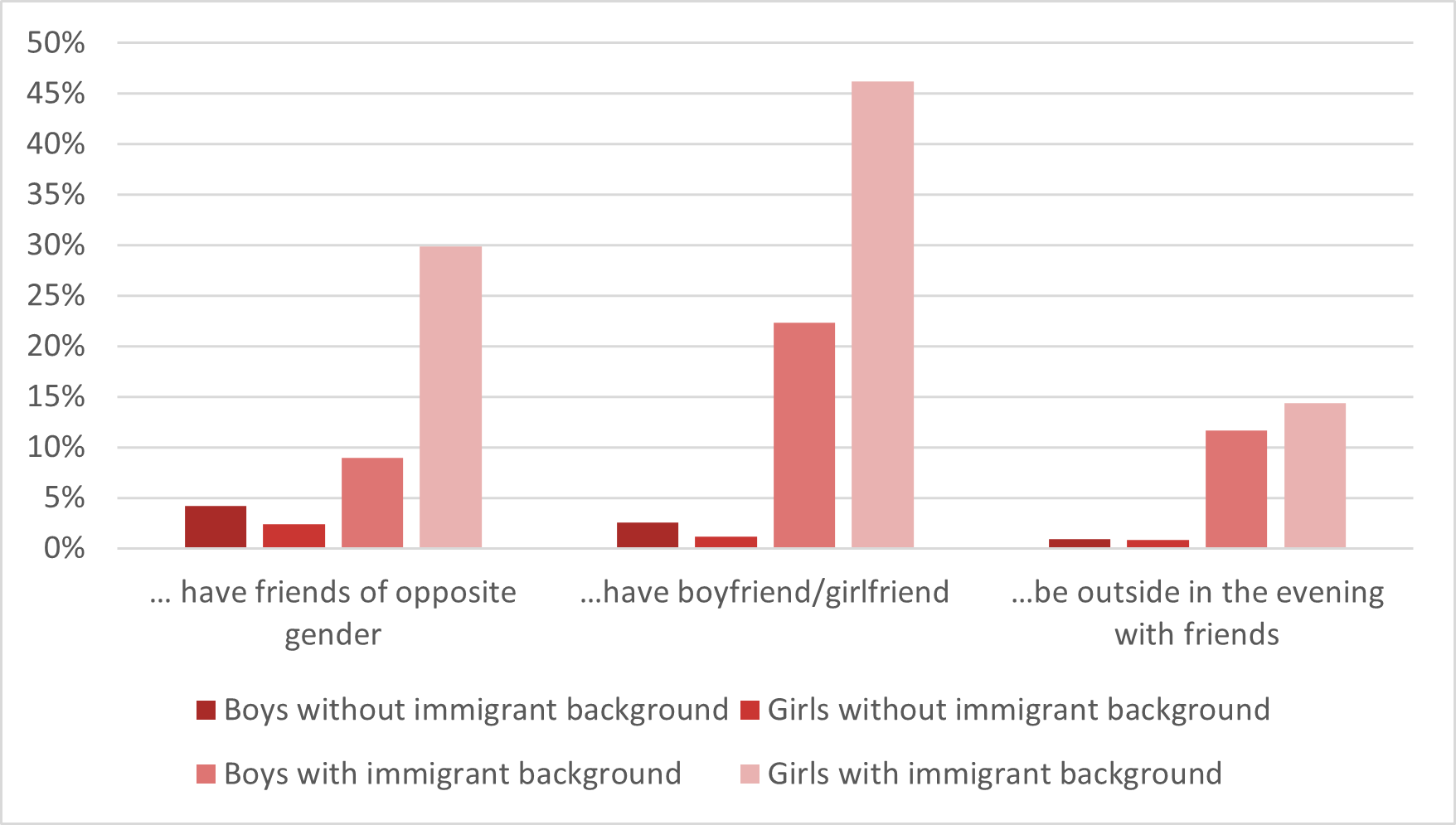

Figure 5.1: The proportion of pupils in the final year of upper secondary school in Oslo (2018) who are not allowed to ... (Smette et al., 2021)

It is also outside the school that researchers find the largest differences between girls and boys with a minority background. It is concluded that parental restrictions on both leisure activities and school are strongly gendered for young people with a minority background. This does not happen to the same extent for young people with a majority background.

Influence over choice of spouse

In Statistics Norway’s survey of living conditions among the immigrant population, married and engaged people under the age of 40 were asked how much influence other people had had on their choice of partner and when they got married or engaged. More than three-quarters of the respondents stated that others had had little or no influence on these choices. The only exceptions were immigrants from Pakistan and to a lesser extent Turkey: 35 per cent of the married or engaged Pakistani immigrants stated that others had had a major influence in these areas. Among the immigrant sample as a whole, this figure was 11 per cent. Among the people born in Norway to immigrant parents, it is also the young people with a Pakistani background who most often report that others had had an influence in these areas. A fifth of Muslims born in Norway to immigrant parents stated that others had had a major influence on circumstances surrounding their choice of partner and the timing (Barstad, 2021).

Minority advisers and integration advisers’ work in 2020

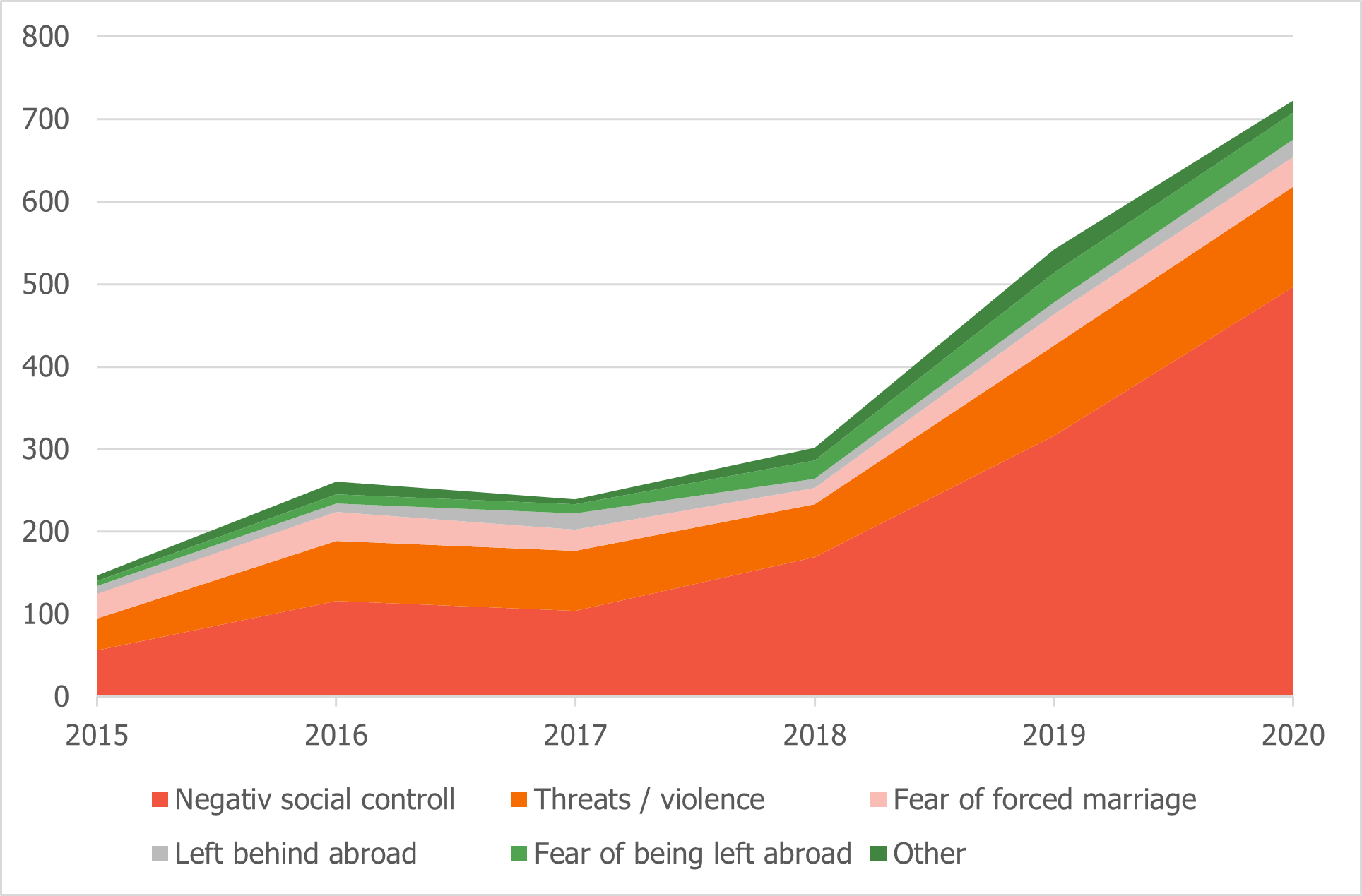

The Directorate of Integration and Diversity (IMDi) has 49 minority advisors, who are deployed at selected lower secondary schools, upper secondary schools and adult education centres throughout the whole of Norway. The role of the minority advisers is to help ensure that more children and young people who are at risk of, or are victims of, negative social control and/or honour-related violence receive advice, guidance and follow-up in line with their needs and rights. In addition, special envoys for matters concerning integration (so-called integration advisers) are stationed at selected embassies abroad. The integration advisers provide consular assistance to individuals who are victims of transnational negative social control and honour-related violence. Over time, the number of minority advisers has increased, resulting in the identification of more cases. In 2020, the Directorate of Integration and Diversity (IMDi)’s minority advisors provided advice and guidance in a total of 723 cases. This is an increase of 33 per cent from 2019. As in previous years, the main problem in most cases concerns negative social control and violence or threats. Most of the cases involve girls, and the cases have primarily involved persons originating from Syria, Somalia, Pakistan and Iraq. The increase in the number of cases from 2019 to 2020 is mostly linked to negative social control and cases concerning girls and women (IMDi, 2020a).

Figure 5.2: Number of cases handled by minority advisers. (IMDi, 2020b)

The work done by the minority advisors was heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. In the first phase of the pandemic, when schools were closed, the minority advisers received fewer inquiries. This was linked to the lack of opportunity for physical meetings and private conversations at school. The second half of 2020 saw a marked increase in the number of cases.

The minority advisers’ experiences indicate that infection control measures are being used as a new control tool against young people who are victims of negative social control. Physical presence in schools is therefore considered crucial in order to be able to follow up children and young people who are being subjected to negative social control and honour-related violence.

In 2020, the Directorate of Integration and Diversity (IMDi)’s integration advisors provided advice and guidance in a total of 250 cases. This is relatively stable compared with 2019. More than half of the cases concerned individuals who have been left abroad against their will. In line with 2019, most of the people who received assistance were girls, and the cases have primarily involved people with a background from Somalia, Iraq and Syria (IMDi, 2020a).

The number of reported cases of negative social control and honour-related violence does not provide an overview of the full scope of these problems. It is likely that there are more cases of negative social control and honour-related violence than those that are captured by the support system today. Nevertheless, the main trend in the figures reported by the minority advisers and integration advisers suggests that an increasing number of at-risk people are being identified and receiving the assistance they need.